benchmarks, hardware, and performance: how much biological inspiration is needed?

published:

The term Neuromorphic computing refers to a variety of concepts and ideas, all falling under the umbrella of things that compute and look like neurons, or more precisely, computing methods inspired by the structure and functions of the human brain (as defined by Carver Mead, see here). Also, Neuromorphic computing has increasingly become a recurring theme in my research. I believe the field has an exciting future ahead. However, like any research area, it has its challenges and limitations, and people are working to address them. For example, a few weeks ago I spontaneously joined at the last minute in the Brain inspiration in neuromorphic computing workshop at the Bernstein Conference, organized by Emre Neftci and Tobias Gemmeke. During the workshop the folks there touched on several interesting points. In this blog post, I’d like to delve further into these ideas. But, quick disclaimer: this is not intended to be an exhaustive or complete review of the workshop - just some thoughts :)

benchmarks

My take is that Neuromorphic computing has struggled to capture the attention of the Machine Learning (ML) community and get significant investments because, you know, it is not good enough. Typically:

- there is always a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) that outperforms it.

- training is too slow, look at how much parallelization I get with my Transformer.

- “What are spikes? Why should I bother?”

In my opinion, these arguments may oversimplify the issue. Comparing different models should be done on fairgrounds. For instance, CNNs that are trained on GPUs are by construction excellent at fast matrix multiplication and thus great for processing static images and identifying statistical patterns within them. On the other hand, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) are recurrent machines that evolve over time and communicate using sparse events and thus being intrinsically bad at processing static images (?). But they could be potentially superior for other challenges. For example, they might excel when applied to energy-constrained problems that require real-time solutions. Unless we don’t care about energy consumption, or draining our planet faster.

The challenge, however, is to identify problems that are best solved exclusively with neuromorphic solutions. Do such problems exist, and if so, what are their defining characteristics?

Guillaume Bellec, from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, emphasized the need to find applications where spikes make the most sense. Guillaume proposed compression as a potential Neuromorphic-friendly benchmark, demonstrating that storing compressed signals in spikes is more memory-efficient than conventional techniques. Essentially, he showed how vector quantization with spikes might provide a fair basis for comparing standard ML and Neuromorphic approaches. That was unpublished work, but keep an eye on your X or Google Scholar or the like as the preprint is coming soon.

Charlotte Frenkel’s talk was inspiring. Charlotte, along with other colleagues, is pushing forward a collaborative approach called “NeuroBench.” In their white paper, they state:

“The rich landscape of neuromorphic approaches supports the exploration of brain-inspired ideas that significantly deviate from mainstream deep learning algorithms and hardware. However, the field lacks a systematic approach to identifying the most promising properties for specific use cases. This lack of standardization underscores the need for objective metrics and benchmarks,” white paper.

Indeed, a Neuromorphic solution can encompass various computational primitives (from leaky Integrate-and-Fire neurons to 3D biophysical models), network architectures (from single chips to clusters of networks), and learning algorithms (from local learning rules to network feedbacks, and even backpropagation through time). Initiatives like NeuroBench may help us pinpoint problems that are best suited for event-based computing, and the best models to solve them. On a side note, Charlotte also demonstrated how to achieve online learning on a small yet powerful neuromorphic processor called ReckOn, pretty interesting stuff.

hardware

Choosing the right problems to solve and optimizing the system are not the only considerations to point out. Ultimately, you want some physical system to behave smartly. This comes with the challenge of dealing with physics, and the noise (entropy) that tries to destroy all your plans. Interestingly enough, you end up trying to solve the same problem that evolution has been facing the whole time: you need to be smart in a constantly changing and noisy environment, move through the different spatial and temporal hierarchies of nature, and use the least amount of resources you can - resources are scarce.

Melika Payvand works at the Institute of Neuroinformatics of the ETH, and in the lab, they are interested in the structural properties of brain circuits, their functional implications, and building better neuromorphic devices, among other interests. Melika emphasized that solving real-world problems requires representing multiple scales, both in space and time. The brain accomplishes this by employing specific computational units at each level of the hierarchy. These units are coupled with sparse connectivity and communication, which is quite distinct from the standard GPUs that primarily perform dense matrix operations. Melika proposes drawing inspiration from this approach. She demonstrates how resistive memories (memristors) are an example of physical substrates that can support intelligence. Memristors are novel physical devices that can change through experience and retain a memory of past events. Melika showed that memristors can represent time effectively and enable networks to adapt parameters in real-time, facilitating problem-solving on the fly.

performance

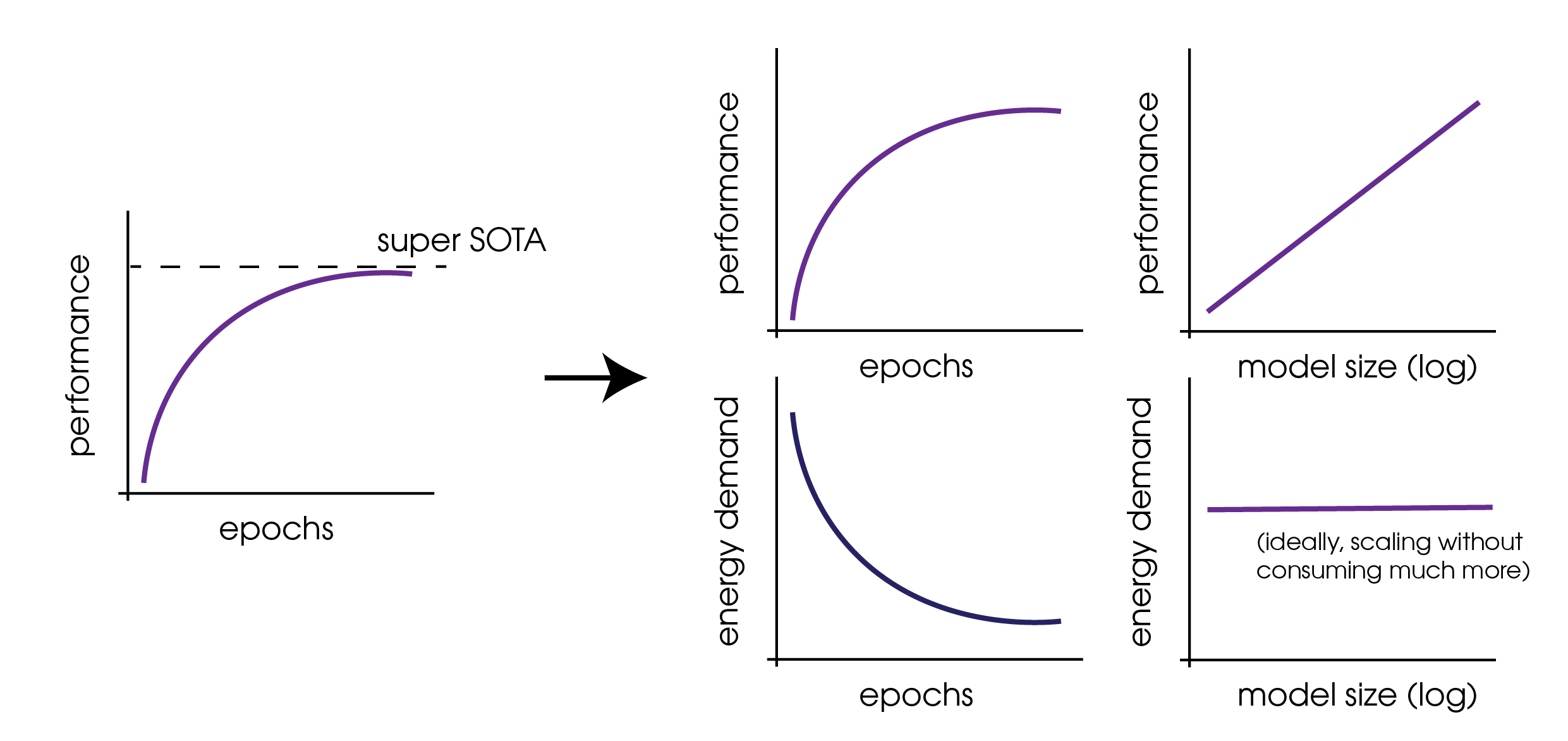

Finally, providing identical initial conditions to multiple players in a game may not necessarily be the fairest option. Similar concepts should work for the Machine Learning folks. When developing novel intelligent systems, it’s crucial to consider multiple metrics beyond just performance. In my view, we should shift from metrics solely based on performance to something in this direction:

This shift in our thinking about learning machines and what we prioritize during their training may lead us down new paths where neuromorphic solutions prove to be the optimal choice. How to reach this point, however, remains a challenging puzzle.